Whale sharks are the largest fish in the world, found in all tropical and subtropical oceans and can reach lengths of up to 20 m. They feed mainly on plankton, but also on squid, small and medium-sized fish, and crustaceans, which they catch in the upper layers of the water with their huge mouths and filter out of the water. Whale sharks reproduce by laying eggs that mature in the uterus. This is also where the young whale sharks hatch and are born alive. However, these impressive animals are highly endangered, as their numbers have declined dramatically in recent years.

It is therefore important to determine how quickly whale shark populations can recover. Very little is known about the animals' way of life, and sexually mature whale sharks are only very rarely sighted. However, an increasing number of adult female whale sharks have been observed in the area around Darwin's Arch, and researchers believe that these may be pregnant animals.

For this reason, marine biologists Chris Rohner and Alex Hearn, together with the Marine Megafauna Foundation team, have launched the Galápagos Whale Shark Project. Their goal is to obtain comprehensive information about the whale sharks' migration routes, diving behavior, and health status. To do this, the sharks are equipped with satellite transmitters that send the data they collect as soon as the fish reach the surface of the sea. The researchers obtain additional information about the animals' health and reproductive cycle through ultrasound scans and blood samples. The data obtained in this way can then be compared with existing information from previous years. This enables Chris and Alex to understand the behavior of the animals and develop appropriate measures to protect these rare ocean giants.

Modern technology makes it possible

Two different satellite transmitters are used to collect data: miniPAT to determine diving behavior and Spot6 to indicate the whale shark's position in the ocean.

By linking the data obtained, the researchers can determine whether the whale sharks' swimming routes are based on features of the seabed, such as fracture zones or seamounts. In addition, both transmitters record the diving depth, water temperature, and light conditions.

During previous expeditions, the researchers found that the transmitters they used worked well down to a diving depth of 2,000 meters, but were then either destroyed by the pressure or fell off. For this reason, four DeepV2 transmitters suitable for depths of up to 4,500 m were tested during the 2019 expedition in addition to the models used previously. All transmitters are attached to the dorsal fin of the whale sharks with a clip, which means minimal invasion for the animals.

The SPOT6 transmitters are designed for long-term tracking of whale sharks and can ideally report all movements of the shark for up to four years as soon as it comes to the surface. The miniPAT transmitter, on the other hand, is programmed to detach automatically after a preset time or depth and float to the surface. Only then does it send the stored data to the satellite. The newer DEEP V2 transmitters have been programmed to detach from the whale shark after 10–40 days and also rise to the surface to transmit their data.

Further Work on the Whale sharks

Blood samples were also taken from the whale sharks. Because the animals have skin that is up to 25 cm thick, special long cannulas and a great deal of skill are required. This is because a whale shark swims at speeds of up to 5 km/h in the ocean and does not simply stand still and wait until everything is over. The researcher must therefore hold on to the shark while taking the sample. This is preferably done on the pelvic fins, as the skin is thinner here.

During the 2019 expedition, four blood samples were taken from what were believed to be adult whale sharks. The scientists later compared these with samples from previous expeditions. The blood samples were mixed with an anticoagulant and separated into blood serum and plasma by centrifugation. Using the blood serum, simple basic values as well as partial oxygen pressure, pH, CO2, and lactic acid values could be determined on board the research vessel. Based on these values, researchers can determine the individual stress levels and general health of whale sharks.

Pregnant or not?

Blood serum and plasma were frozen for further analysis in the laboratory of the University of San Francisco de Quito. Among other things, the concentration of various sex hormones, such as estrogen, progesterone, and testosterone, is being determined. Since there is still no precise knowledge about the sex hormones of adult whale sharks, these values are very important for determining whether the animals are fertile, pregnant, or even sexually mature in the future.

Although none of the animals showed signs of pregnancy or receptivity to mating, the values suggest that the whale sharks off the Galápagos are of reproductive age and may have recently given birth to young pink iguanas.

This is also supported by the fact that whale sharks begin to arrive in large numbers in the Galápagos Marine Reserve in June. Most of the animals are there in August and leave the reserve by December. The researchers therefore hope that they will be able to detect different hormone levels when the whale sharks arrive in June.

Where do Sharks migrate to?

All five SPOT6 transmitters transmitted reliably and provided the researchers with further insights.

- · The first tagged whale shark covered a distance of more than 3,426 kilometers in 66 days, swimming from Darwin's Arch in several loops around the Galápagos Islands until the signal was lost in the waters far east of the archipelago.

- · The second whale shark covered a distance of more than 2,407 kilometers in 149 days, swimming from Darwin's Arch to the deep waters north of Peru, where the signal ended.

- · In 21 days, the third whale shark swam 1,185 kilometers towards Peru. In an area with water depths of up to 3,500 meters, the signal was lost for unknown reasons.

- · The fourth whale shark swam a distance of 1,811 kilometers in 58 days from Darwin's Arch to the coast of Ecuador, where the signal stopped.

- The fifth whale shark, named “Esperanza” (Hope), covered a distance of over 7,408 kilometers in 224 days. This is the longest migration route ever recorded by satellite for a whale shark. Researchers hoped that the whale shark would continue swimming eastward (which would have been the first evidence of a “round trip” back to the Galápagos Islands). Instead, the animal swam west toward French Polynesia, where the transmitter has not transmitted any data since the end of May 2020, after 270 days.

Unfortunately, all transmission signals from the whale sharks disappeared in unprotected waters. The presence of huge Chinese fishing fleets around the Galápagos Marine Protected Area is a particular cause for concern. These ships indiscriminately fish anything that gets caught in longlines and nets. They are therefore a major threat to biodiversity in the Galápagos Marine Protected Area.

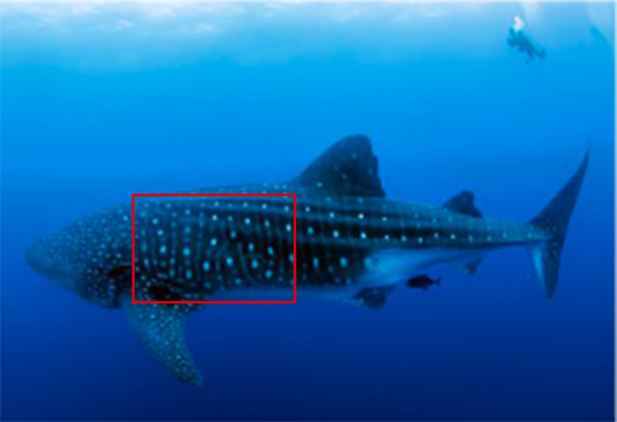

A global database of whale shark images

The skin pattern of whale sharks is unique to each animal, comparable to our fingerprints. For this reason, Chris photographs all the whale sharks he sees and uploads the photos with the date and location of the sighting to the international whale shark database “Wildbook for Sharks”

https://www.whaleshark.org/. This database allows divers to identify animals or determine whether and where an animal has already been sighted. During the 2019 expedition, 33 whale shark photos were added to the database.

This data also helps researchers determine how long the animals stay in the Galápagos Marine Reserve around Darwin's Arch or whether they leave the area and return. It is also hoped that this will enable researchers to deduce the behavior of whale sharks or areas that meet the specific needs of the animals, such as foraging, birth, and rearing.

Over 550 whale sharks from the Galápagos archipelago alone have been added to the database so far. This has been made possible by local diving schools and divers who have agreed to actively support this photo campaign.

New Challanges

Long-term data on the migration and lifestyle of these animals is urgently needed to gain further insights into the life of whale sharks. Only then can effective protective measures be developed.

To this end, it is important to find transmitters that work at depths of up to 5,000–6,000 meters to replace the miniPAT transmitters used to date, as these detach or are destroyed once a diving depth of 1,700 meters is reached. Unfortunately, there are currently no tested transmitters that meet these requirements. The team is therefore in contact with developers working in this field. Until a solution is found, the tried-and-tested transmitters will continue to be used.

The team is also considering attaching an accelerometer to record different types of movement (gliding, vertical diving, swimming in circles, and surfacing).

The blood samples will be compared with those of other whale shark populations worldwide. In the future, it is planned to coordinate the data analysis with that of the team at the Georgia Aquarium in Atlanta, as they also examine the animals' blood for nano-plastic particles

As you can see, there are still many gaps in our knowledge before we know enough about these unique and majestic giants of the sea to ensure their long-term survival.

Kommentar schreiben